HIDDEN XÀBIA – The Customs Barracks of La Granadella

This year, the last remains of the old customs guard barracks in La Granadella were demolished to expand a rough parking zone.

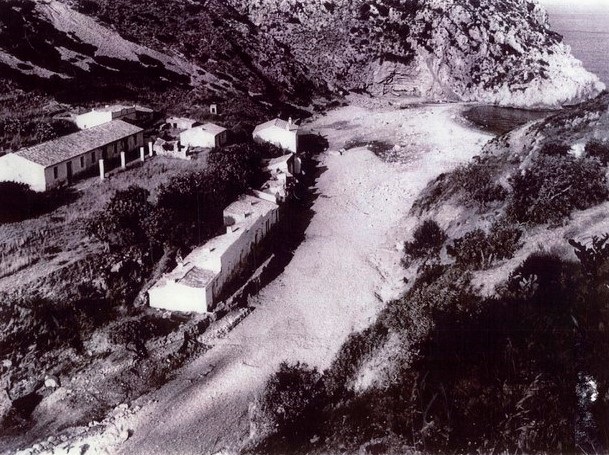

Coastguard Barracks, on the left, above the beach of La Granadella

Monday 27th December 2021 – DAVID GUTIERREZ PÁLIDO with Mike Smith

Recently we have been able to learn how the few ruined walls that peeked through lush vegetation in the parking area in La Granadella have disappeared due to the expansion of said dirt car park. Although they could pass perfectly as the ruins of a country house, of the many that still stand, it was actually a building that housed the Granadella customs station. With this excuse, we will remember some stories collected in the historical press about it1.

The Royal Corps of Coastal and Border Police was founded on March 9th 1829 by Royal Decree of King Fernando VII. However, the origin of the carabinieri dates back to the 18th century when Felipe V founded a brigade and later, Carlos III, expanded some ordinances of his body in 1770. The main function of the carabinieri was to monitor the coasts and borders for tax fraud and smuggling and it was for this reason that the barracks were built throughout the 19th century along the coast of Spain. The Marina Alta, and specifically Xàbia, was not exempt from having several barracks houses such as those of La Granadella, Ambolo, Portitxol, Las Planas or next to the Grava beach (in the place where there is the Plaza Maruja Varó today).

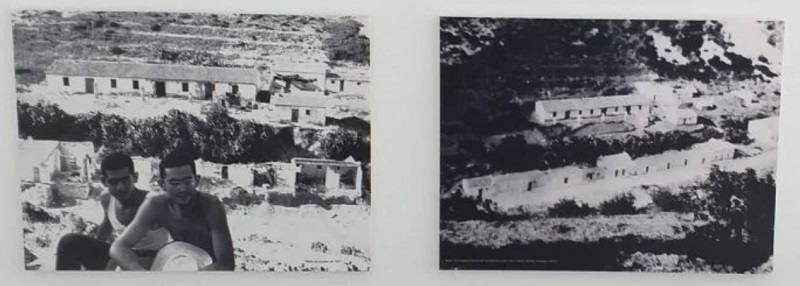

That of La Granadella, which we suppose were built during an undetermined date in the 19th century, were three simple, one-story, terrace row of houses, built of stone and whitewashed. On the facade the building had a central door with two windows on each side and covered by a gabled roof. The carabineros deployed here lived there together with their families, who between the years 1871 and 1880, we know were Francisco Castell, José Samper and Vicente Such, being the oldest reference found.

Another of the prominent police officers based in La Granadella was Francisco Ferrandis, who was born in 1871 in Planes (Alicante) and who was deployed to this position in 1911 who stood out, along with his wife, for having created a school in area. The Xàbia doctor, Jaime González Castellano, highlighted this in an article published in Las Provincias on November 19, 1911 in which he wrote:

“Thanks to the detachment and diligence of Ferrandis, the children of the police and fishermen of the aforementioned point receive an education that has nothing to envy that given in the official schools mounted, and the difficulties presented by the great distance that mediates between La Granadella and the population, to attend the young schoolchildren in public schools ”.

Boys were taught “the elementary knowledge of the religious, moral or intellectual education of the child, in accordance with what pedagogy advises“, while his wife instructed the girls “in the principles of the Christian religion, in domestic chores and above all, in the art of sewing, cutting and ironing”. For this altruistic work, Ferrandis and his wife did not receive any retribution, they only accepted firewood for cooking from the children’s parents.

The Carabinieri disappeared on March 15th 1940, when it was integrated into the Guardia Civil. Their characteristic dark blue collared uniforms were transformed into green uniforms and, although the houses continued to be used, they were ultimately the product of neglect and continued deterioration. Today these small ruins have already disappeared, but at least we can remember some of these stories that occurred in them.

But not all is lost, since in Les Planes, the remains of the other barracks still stand. Can we save it and get it back?

David Gutiérrez Pulido

(Ldo. Historia del Arte)

www.sorollajavea.wordpress.com

1 This article has been prepared thanks to the information of two magnificent articles: CODINA BAS, Juan Bautista: “La vida laboral de Jávea entre 1871 y 1880 (IV)” in Canfali Marina Alta, June 29, 2013 and ERADES, JF: “Carabiners: Moralitat, lleialtat, valor i disciplina” in Festes Mare de Deu de Loreto, 2014, pp. 60-72. Thanks also to the conversations with Juan Bautista Codina Bas and Godofredo Cruañes Aracil.