One of Xàbia’s most famous stories is the murder of five-year-old Bartolomé Sendra by his stepmother Úrsula Tachó in 1920 which has become etched into the collective memory of the town.

Several books have been written about this infamous character known as ‘La Criminala de Xàbia’, a film has been made, and the town hall has even developed a theatrical guided tour in the port to mark the centenary of this gruesome tale, one which remains well-known by Xabieros, but not known so much by those from beyond who have chosen to make Xàbia their home.

Here we have written an abridged version of events as told by author Bernat Capó in his book “La Criminala” published in 1986, with additional information from “La Casa de la Criminala” by Erika Reuss Galindo, published in 2019 in the fiesta book of the port fiesta.

Modesto Sendra was a policeman stationed in Xàbia, responsible for guarding the coast against smuggling. He had been married to Leanor who had borne him two children, a daughter and a son. But Leanor had died giving birth to the boy, who was named Bartolomé, and Modesto was left a widower. With the children packed off to live with relatives in Gata de Gorgos and Teulada, he lived alone for a few years before meeting a women called Úrsula Tachó, daughter of a retired Guardia Civil officer.

Úrsula had been a strange child, a bit of a loner who was subject to temper tantrums that meant that she made few friends. When she met Modesto, her parents saw it as a chance for her to make a new life for herself. They married and went to live with her parents in Portitxol. After a while, Modesto decided that Bartolomé should come and live with them. He was five years old.

Úrsula’s mood changed after the boy arrived. She appeared to grow jealous of him, especially once she fell pregnant with her son. Like any normal five-year-old child, Bartolomé wanted a little attention, a smile, and a cuddle. When his father was working, the boy received attention from Úrsula but it proved to be that of hate and violence. When her mother took pity on the boy, Úrsula would scream at her to stay out of her life, and when her husband returned home from work, he would have to listen to a long list of grievances from his wife. But he refused to challenge his son.

Thus, she determined to get rid of the boy using all means at her disposal. After changing tactic and winning over the boy’s trust, she took him to pick herbs amongst the pine trees and thick undergrowth of Cabo La Nao. After suggesting they play a game of hide-and-seek, she watched as the boy ran into the distance to hide behind a bush before turning around and making her way back to the house in Portitxol without him. When her mother asked on the whereabouts of the child, Úrsula screamed at her that she didn’t care and went to her room, where she caressed her growing bump, assuring her future child that it would be the only one.

Bartolomé appeared at the door of the house the following morning, his clothes torn and arms and legs covered in blood. He quietly washed himself in the sink and then went to his bedroom. Later the same day, he emerged to find Úrsula and her parents eating lunch around the table. The woman dropped her spoon in shock, for she had just seen a ghost. Bartolomé started crying for his father, who was sleeping having returned from work earlier that day. Modesto appeared, rubbing the sleep out of his eyes, and calmed the boy, telling him that he had to be more careful when playing in the woods.

Úrsula’s second attempt was none too subtle. Asking the boy to help get water from the well, she pushed the child into the abyss, before fleeing in mock horror to seek help in the secret hope that Bartolomé would drown in the meantime. But the boy’s luck continued to hold and the rope had caught on the pulley which had held the bucket just out of the water. He climbed onto the bucket and shouted for help, his screams heard by a man who carefully pulled up the boy from the well. Úrsula appeared and accused the boy of being a rebel, a brawling mischievous devil who would end up breaking her nerves and causing the miscarriage of her unborn son. But Bartolomé looked at her with big, accusing eyes, and she fell to the ground in fear.

When Modesto returned home, his wife told him how Bartolomé had threatened her and that she could no longer bear so many scares, that he should punish the child or take him away elsewhere for he would cause the loss of the baby. The father took a belt in anger and entered the room where Bartolomé was sleeping. He shook the boy awake. He opened his eyes, gave out the sweetest smile, and hugged his father. Modesto dropped the belt, he couldn’t do it.

Days later, Úrsula gave birth to a baby boy who they named Francisco and she gave strict orders to Bartolomé that he couldn’t come anywhere near his brother. And she prepared her next attempt to get rid of the boy.

As the woman suckled her son, she saw how jealous Bartolomé appeared to be and that gave her a new idea. She made some soup into which she crumbled broken glass and some match heads and offered it to the boy, her eyes blazing with murderous fever. Asking if he found it good, the boy replied that it was so, but seemed a little dirty. He finished the soup and went out to play. His stepmother watched him closely for several days but nothing happened. She offered more soup but it seemed that the boy had a strong stomach so Úrsula had to engineer the last and final test.

For some time, she had been telling her husband that his son was a secret smoker who used paper and dried leaves for tobacco. She saw her chance. One night, she approached the sleeping boy and with all her strength, she squeezed his neck and strangled him until he was dead. She then took out a knitting needle from her apron and pierced the child’s eardrums, before making a cigarette, lighting it and dropping it on the mattress which caught fire. She placed a box of matches on the shelf and left the room.

Modesto arrived home from work the following morning to be told by his mother-in-law that his son had died. He found the body of the child wrapped in a blanket on the floor of his bedroom, his eyes still open. In tears, he picked up the body and embraced his dead son as he walked out on to the terrace. He asked for Úrsula but no-one replied. He asked again, more forcefully, and still no-one replied. For Úrsula had already been taken away by the Guardia Civil.

The forensic report confirmed that Bartolomé had not burned to death or suffocated from the smoke but had been strangled. It also confirmed the use of something sharp to pierce the eardrums. The autopsy found remains of glass and a flammable mixture in the boy’s stomach similar to that used to make matches. It concluded that the boy have died in terrible pain.

She was convicted and placed in a women’s prison but was released at the beginning of July 1924 thanks to a general amnesty decreed by General Primo de Rivera and sent to a psychiatric hospital run by nuns. She was released after just a few months and went to live with a very rich man as his housekeeper. On his death, Úrsula inherited his fortune and returned to Xàbia a rich woman. By this time, Modesto was a changed man and had requested a transfer to Dénia. Unsurprisingly, he didn’t want anything to do with his wife.

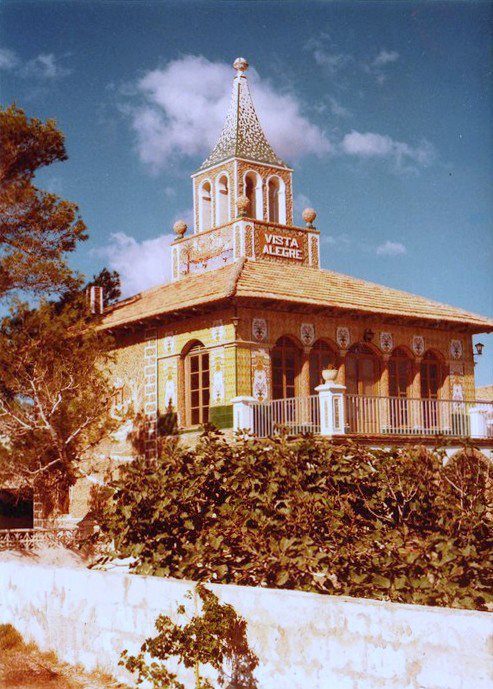

Úrsula commissioned the construction of a chalet on the Primer Muntanyer, one of the first to built in the area and located close to where the current Hotel Sol de Jávea is now. It was an unusual house, covered in tiles which created all sorts of images, typically of the Valencian countryside and was called ‘Vista Alegre’.

She employed two housekeepers called Josep and Remei who she treated very badly and the two parties constantly argued over money for she refused to pay them the salary which she had promised them. At one point, she promised to name them as her heirs, though this didn’t help much since her son Francisco was still alive.

Francisco had become a quite unstable young man who had tried unsuccessfully to join the Guardia Civil. He received no help from his mother but on the death of his father, he received a contribution from the service which helped widows and orphans of the deceased. Since Úrsula had been prosecuted and sentenced, the money went to Francisco and he bought a horse and cart to try and become independent and start a new life. One day, whilst on his way to a construction site, his cart, which was loaded with beams, lost one of its wheels, started to stagger and hit the young man’s back, causing him to fall to the ground. The other wheel crushed his neck, causing death by strangulation. It is not known if Úrsula was moved by his demise.

For Úrsula, her fate was approaching. Her housekeepers had become tired of the fact that the people of Xàbia avoided them due to their connection with her and had decided to move away to another place where they would not be ignored when they greeted people. Josep approached his mistress and told her of their plans. She replied that she thought that they had been well looked after, to which he replied that they had been with her for almost two years but had only eaten and drank, there was never any money. She reiterated her plan to make them her heirs, but they refused to believe her, so she promised them some money.

For some time, they waited but no money came their way. Josep once again approached Úrsula who implored him to be patient and that everything would be theirs soon enough. He replied that they heard the promises but never saw the money. She accused him of being insolent and warned him that it would cost him dearly.

Later that same day, Úrsula closed her eyes and never opened them again. An enraged Josep had been blinded by his anger and had taken a club from beside the hearth and struck his mistress on the back of the neck which such force and rage that it snapped and killed her.

Josep was sentenced to 30 years in prison whilst his wife Remei travelled to France, returning to Xàbia some time later where she lived until her death in 2016. As for Josep, he disappeared after serving his time in prison and nothing was heard from him again.

The Villa Alegre stood abandoned for several years and was subject to many stories about ghosts and apparitions; it was said that terrible cries from a child could be heard at night. When it was converted into a cocktail bar, it was called ‘La Bruja’ but it didn’t last long. The building was demolished in the 1980s.